Sponsored By

ROCK

HARDWARE

Interview: Chris Dewhirst

[ More Interviews ]

Date:

1st Jan 2004

Intro: Chris Dewhirst was at the forefront of climbing in Australia

during the late 1960's to early 70's. He put up many hundred first ascents

some of which are now recognised as classics such as Manic Depressive

(15M3, now 25) in the Grampians, Skink (16M1 now 17) and Werewolf

(possibly the first grade 20 in Victoria) at Arapiles, the pen-ultimate

Victorian aid routes Ozymandias (M4 now 29) & Lord Gumtree (22 M6) at Mt

Buffalo and the impressive Conquistador (20) on the East Face of

Frenchman's Cap in South West Tasmania. Visiting the US he became the

first Australian to conquer the 5.11 grade and is acknowledged as having

bestowed chalk upon Australian climbing. Chris has been an actor in films,

including an award winner entitled 'Just Another Climb' depicting a

mountaineering tragedy. He's run "Adventure Travel" a market leading

business specialising in Himalayan trekking holidays and other pursuits.

However for a number of years his career and interests have revolved

around ballooning. He holds the Australian high altitude balloon flight

record of 36,600 feet and led a combined British and Australian expedition

on the first successful balloon overflight of Mt Everest. His business "Balloon Sunrise",

which will take you, by Balloon, over Melbourne, Nepal or even Everest

itself.

| Notable First Ascents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In 1964 I was in year 10 at high school and my best friend was John Moore (still a close friend, living in Melbourne and now making independent films - usually of a documentary and historical nature). John was very innovative and adventurous - more than me. I was an ardent follower of Johns ideas and easily led astray. We became interested in falcons and collected a few, including some peregrine falcons obtained by robbing a nest at Kinglake National Park. This involved extremely dangerous manoeuvres dangling from the end of a coir rope and swinging into the nests. Another schoolboy friend was also involved - Phillip Stranger and the three of us collected goshawks (from Hanging Rock), Kestrels (from the Organ Pipes) and Peregrines from Kinglake. Phil was terribly injured a couple of years later on Mt Wellington above Hobart.

Our main interests were falcons,

bull fighting and later in that year rock climbing. We were very confident

that we were the only falconers, bullfighters and climbers living in

Australia. Our information was obtained by reading books borrowed from the

Melbourne library. The most formative climbing books were ‘Conquistadors

of the Useless’ by Lionel Terray (by incredible chance I met Terray’s son

one day while I was sitting behind a desk at ‘Adventure Travel’ in Sydney.

A man walked into the office selling ‘T’ shirts embossed with logo’s. It

was extraordinary that this young man was the same person held aloft by

his father shown in a photograph in Terray’s book - a most remarkable

chance!). The White Spider by Harrer, a book by Gaston Rebufet (?), Nanga

Parbat pilgrimage by Herman Bull and other European climbing books were

very inspiring.

We learned to abseil (incorrectly) by using pictures from Gaston Rebufet’s

book.

The Melbourne library was attached to the museum and one day while

trawling through the museum we noticed a picture of the Organ Pipes at

Jackson's Creek. We decided to find the Organ Pipes and walked the length

of Jackson's Creek over three days until we discovered them. My first back

pack was a plastic rubbish bin that I roped up with back straps. Ugly but

efficient. John and I made our packs, tents and sleeping bags - we were 15

at the time. We climbed extensively on the Organ Pipes and went back a

number of times. We were getting ready to climb the north face of the

Eiger.

Early on we cut down much of the bush that grew out of the Pipes. We spent

a lot of time cleaning the cliff to make the climbing more aesthetic.

Although on one occasion we attempted to push a lose boulder from the top

of the cliff to find a whole 20 metre high column collapsing! Preservation

of the environment was not a high priority in the 60’s. Although a little

later the fight for Lake Pedder changed my thinking.

To do our climbing we purchased a 250 ft coil of 9mm laid nylon rope from

a ships chandler and this became our climbing rope. We manufactured our

own pitons from angle iron. We used hacksaws and a steel lathe. Our

‘piton’ hammers were purchased from the hardware store and our carabiners

were made the same way and later purchased from a ships chandler.

We had been climbing a year on the Organ Pipes, Cape Woolomi, Hanging Rock

and various other places that we could walk or hitch to before

encountering other climbers. We bumped into Chris Baxter, Bob Bull, Peter

Jackson, Mike Stone and Reg Williams on a very memorable day at Hanging

Rock. I do not know who was more surprised.

Q: Dare I ask about the gear you climbed

with back then? I'm assuming we can forget cams, modern belay devices, and

high performance sticky rubber shoes.

In the 1960’s there were three types of protection: Don’t fall off was the

first type. The second type was don’t fall off but involved looping slings

over rock projections in case you did and the third type was pitons. One

day in 1965 or 66 Bob Bull arrived at Arapiles with an engineering nut -

drilled out - and threaded onto a sling. This was the first artificial

chock I had seen. I remember Bob Craddock (at the time Craddock was

president of the VCC) saying that it would not change climbing. Within 12

months climbing grades went from 14 to 19 and the number of new routes

began to grow almost exponentially. Climbing became much safer. After

seeing Bob Bull’s new chock John and I went home and drilled out dozens of

nuts of varying diameter. I took a long fall from a new route on Tiger

Wall when a hold came off and a tiny little nut took the fall. I can’t

remember the name of the climb but I can clearly remember the route in

good detail. And I am sure the nut is still in place slowly rusting away.

We understood the need to belay properly by tying off to multiple points

but we did not have friction belay devices. John Moore held a very big

fall that day on primitive equipment and his belay was sound. In those

days we tied directly onto the end of the rope.

The quality of protection and the quantity of protection evolved with the

difficulty of the climbs. I started climbing in Dunlop volleys and later

ordered a (fairly large) pair of climbing shoes from somewhere in

Europe. They were psychologically better than the volleys but probably

more dangerous. They quickly became known as the ‘boats’.

We also experimented with making our own shoes by gluing tyre rubber onto

running shoes. It wasn’t until I had been climbing for more than two years

before I obtained a set of friction boots.

Q: What was the style of climbing like

in the early 70's? I'm imagining bold run outs and a total absence of

sport climbers.

No, I do not remember it like that. There were the occasional ‘bold’ run

outs - and I remember a few on Frenchman’s Cap. By and large we made every

effort to protect our climbs. This involved bolts when nothing else

worked. Although there were not many climbers about. In the 60’s perhaps

10 climbers on a busy weekend at Arapiles. In the early 70’s this had

grown to 40 or 50 climbers on a very busy weekend.

We were focused on ‘secret’ new routes and intense competition between

friends to be first up a new climb. This sometimes led to using a point of

aid when it really wasn’t necessary. There was a tendency to bring the

climb down to the climber’s level rather than improve one’s skill to make

the climb without aid. I was guilty of that.

Q: What about the ethic of the day. Was

sieging routes into submission considered acceptable? What about top rope

inspection?

I can only remember being involved in one ‘sieged’ route and that was at

Mt Buffalo on Fuherur. This climb was a shambles because the group was so

inexperienced. Perhaps seiged is the wrong word. We needed three nights

out to climb 400 feet! Later I went back and soloed the climb in a day. I

do not think that seiging was a big part of the times. Although there were

a number of climbs that remained unclimbed classics for a long time -

Usually there were six or more attempts before a ‘hard’ climb was done.

Blimp (20) was an example of this. Blimp is a very nice looking corner at

Bundaleer. It was first attempted by Peter Jackson and Bob Bull. Peter

declared it the last great problem of the 20th century. I had at least two

shots at it before eventually Bruno Zielke led the climb cleanly and I

followed him up. It was two years from being identified to being climbed.

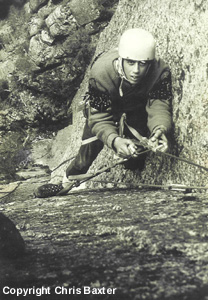

Right:

Chris Dewhirst approaching the second belay on the 1st ascent of

Ozymandias, Mt Buffalo, 1969. Photo By Chris Baxter.

With Ozymandias and Lord Gum Tree we just did them cleanly with one night

out on the face. At the time they were relatively long aid routes but done

without much fuss - except Chris Baxter gave his film of Ozymandias to the

Sun Herald and we got our 15 minutes of fame.

I am trying to remember if I looked at many routes from a top rope. A few

perhaps but it did not seem unethical at the time to inspect a climb.

Although it was unethical to place protection from a top rope.

For example, I never considered climbing Blimp with a top rope then going

back and leading it - so I suppose there was an ethic in place against

doing it that way.

The ethic of the day was to do as many new routes as possible on a weekend

- preferably without aid and there was no time for top roping first.

Quantity of ascents over quality of the ascent was more the momentum of

the day - although we always had a good eye for a quality route.

Q: Overseas climbing trips are taken by

many current climbers, but then overseas travel is a big part of modern

society. Society was different in the 1970's, with the public in general

less likely to travel overseas. In the 1970's, you travelled to the USA on

a climbing trip. Why did you go, and what did you learn? Was there much

difference in standard between US and Australian climbing at that time?

In 1974 I visited the US and Europe on a climbing year out. It was the

first time that I fully concentrated on climbing and I lived in Yosemite

for 3 or 4 months. I arrived at ‘Camp 4’ and set up a permanent spot and

then walked up to one of the small outcrops to check out the scene. I knew

no one at all and I had no particular ‘personna’. An American (Rob Frick)

had just led a 5.9 crack and his second could not get up. Later on I

climbed the Salathe with Rob.

On the day I met Rob he thought I was just an Australian visitor who could

possibly be used to follow and clean the pitch. I thought the climb looked

fairly easy and I definitely wanted to make sure that I made it look easy

because there were at least a dozen local climbers looking on. I climbed

it fast and I know at the time I made it look easy but in fact it was

desperately hard! In my mind it was a solid grade 20 (when 20 was hard!!)

but I told everyone standing around that it was about grade 15 in

Australia. In fact the best of the Americans were climbing at grade 24 and

25 (5.11) when I was climbing at 20/21.

This was my introduction to climbing in Yosemite and it was a great time

in my life. I think one of my most difficult climbs was on Middle

Cathedral. It involved a series of 5.10 moves on a 50 ft run out. I

climbed the Salathe and the Nose on El cap with two nights out on each

climb and both in bad weather. It took two attempts to get up the Nose and

I made a desperate retreat from well above the pendulum in a terrible snow

storm. It seems extraordinary to me that these two routes have been done

(together) in a day and without aid. The level of skill and speed and

understanding of one’s own abilities in today’s climbing world has moved

outside my imagination.

The skill levels in the US in 1974 were beyond what we had developed in

Australia. However I was able to take my own skill from grade 20 to grade

24 in three months of exposure to US climbers while I was in the US.

Q: You are reported to have been the

first Victorian (Australian?) climber to use chalk for climbing. Where did

the inspiration for this come from?

Chalk was common in the US and was used on the East Coast of the States

more than in Yosemite. It was very useful and I took to it immediately. A

drop of moisture on the finger tips can make a big difference and chalk

took it out.

Q: Did you expect / experience any

backlash for your use of chalk?

To be honest it is hard to remember what reaction people had to chalk in

Australia. I knew it made a difference at the level people were climbing

at in the States and in the UK. I think it was adopted in Australia

without much controversy. Obviously I didn’t invent chalk and I think it

is irrelevant who brought it to Australia - it was going to happen sooner

or later. I think it is a necessary climbing aid - like friction shoes

with the right quality rubber. Although it leaves its mark and shows the

way on a hard climb.

Q: I understand that the first

ascent of the famous Ozymandias (14M5), completed in 1969 by yourself and

Chris Baxter, was immortalised on the front page of the Sun newspaper, and

in that famous climbing magazine!? The Australian Women's Weekly. Is this

true, and did you become somewhat of a celebrity as a result?

Only in my own mind. In fact it caused a problem at work because I had not

realised that photographs had appeared in the press and I was on the climb

on a working Monday and called in ‘sick’ - only to find my ugly face on

the front of the newspaper. I was caught out very badly.

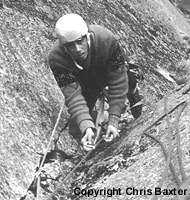

Right:

Chris Dewhirst approaching the forth belay on the 1st ascent of Ozymandias,

Mt Buffalo, 1969. Photo By Chris Baxter.

Q: Do you have any enduring memories of

the first ascent of Ozy? I understand there may have been a bit of

subterfuge involved in the organisation of the ascent, particularly

involving the Gledhill brothers who may also have been interested in the

line. Care to cast any light on this?

It was a long time ago. I can only remember the climbs that I would have

liked to have done first and had ‘stolen’ from me. This includes the Rack

at Arapiles, De Gaul’s Nose on Frenchman's Cap, the Blade on Federation

Peak, Orpheus at Arapiles (we did Checkmate to make up). I cannot remember

the Gledhills being interested in Ozy. In fact we did Lord Gumtree quite a

while after Ozy and in my mind Lord Gumtree was the most obvious route on

the north wall of Buffalo.

Q: Your first ascent of Lord Gumtree

(M6) on the north wall of the Gorge at Mt Buffalo in 1971 would rank up

there as one of the best feats of aid climbing in Australia. Is that a

route you look back on with particular pride?

I really liked the style we did it in. It had a really good feeling and I

enjoyed every minute of the climb - even the fall when a skyhook peeled

was fun. The line of bolts creating the two tier hammocks position was

fantastic. Pete and I slept well and we handed food and drink up and down

the bivvy. Lord Gumtree is nothing compared to the big granite faces in

Pakistan, Yosemite, Baffin Island, Norway. Just a small step in Victorian

climbing and I believe it has been climbed free and in a couple of hours!

Q: In an article in Rock magazine (issue

25), Queenslander Rick White hints at a bitter rivalry between Victorian

and interstate climbers in the late 60's / early 70's. In particular he

seems to point the finger at yourself and Chris Baxter. Do you feel that

there was a rivalry, and if so what was its basis?

I think ‘bitter’ is a little over the top. I remember feeling that Rick’s

hard routes on Frog Buttress could not be as hard as some of my routes of

the same grade - in fact they were as hard or harder! There was definitely

an edge to the rivalry and at the time I am sure there was no better

climber of cracks than Rick. I didn’t want to believe it. Probably well

deserved envy from my side.

Q: Was there a sense of resentment

towards interstate climbers who climbed routes considered to be "last

great problems" (eg John Ewbanks ascent of The Rack (18) at Araplies, and

Joe Friend and Ian Lewis ascent of Blimp (20) at Bundaleer)?

John Ewbank was god and it seemed natural that any climb I had attempted

and failed on would be climbed by Ewbank if he turned his attention to it.

I liked Joe Friend and I cannot remember meeting Ian Lewis but I think

that Blimp was first climbed by Bruno Zielke - perhaps you could research

that for me.

I teamed up with Ewbank on new routes at Frenchman's Cap and on the Organ

Pipes on Mt Wellington. John Moore and John Ewbank were very close friends

for some time so I cannot remember anything but great respect for Ewbank -

in fact awe is probably the better word.

Q: Gerontian (17) at Bundaleer was

climbed by yourself and Peter Jackson in 1965. By today's standards (with

modern protection) this is not a difficult route, nor are some other routes you

put up, such as Werewolf (20) and Death Row (18) at Araplies. However, at the time

you climbed them, they were at the cutting edge of free climbing. Could

you give an indication of the style in which you climbed these routes, in

particular what climbing equipment would have you had on your rack?

I am sorry to say that I cannot remember Werewolf at all - although I am

sure that if I stood below it I would remember every detail. The climb and

the name of the climb have separated in my mind. I remember Death Row very

well and I climbed it pretty well straight up with Phil Stranger cleaning

and following. At grade 20 the climbing was not really very difficult by

today’s standards so if I was in a good mood then I would climb these

things straight up. We were doing boulder problems at grade 25. I would

carry 6 drilled out engineering nuts and maybe 6 pitons and a hammer on

every climb.

Q: Judging by the volume of new routes

you completed, you obviously had a great passion for climbing. You were

also at the top level of the sport. Yet in the mid 1970's you seemingly

walked away. Why?

I also had a great passion for kayaking and in 1975 I was deeply involved

in teaching. I was operating a parallel existence to climbing and although

I still climbed right through the 70’s I had switched intensity to

kayaking. I started a secondary school in Victoria in 1972 (Sydney Road

Community School) and I worked in this school through to 1979 (except for

a climbing year out in 1974). During this period I started a number of

students climbing but it was much easier to run groups of 10 students with

kayaks than to take 10 students climbing. As an adrenaline substitute

kayaking took over. I also became slightly less self centred and became

more interested in the lives of my students than in pushing climbing

routes. My interests expanded into totally different areas and I no longer

needed climbing in the same way. I remember a winter flood trip kayaking

down the Mitta Mitta river (before the dam) as fondly as I remember Lord

Gumtree.

Q: Did you stop climbing "cold turkey"

or have you made the occasional foray onto the rock since? If yes, how is

the form.

Suffice to say that Chris Baxter would no longer need a tight rope from

me! I would love to go climbing again but I have not touched rock for

perhaps 15 years. I keep promising myself (and John Moore) that we should

hit the rock again.

Q: You must have had your share of

epics. Do you have a favourite "there I was" story?

Countless epics. The first serious epic was with John Moore on Federation

Peak when we were 17. We were retreating from somewhere above the blade

ridge and attempted a blind abseil, hoping that the ropes would reach a

stance after we flung them into the abyss. John threaded a sling around a

chockstone and started the abseil. He went down 15 metres until he could

see the ropes dangling free and the ends at least 50 metres above any

stance and 10 metres clear of the cliff - a very bad abseil. He climbed

back up the rope and just as he reached my sitting position the abseil

rope pulled through the chock. The moment still haunts me today. That was

in 1966. My last climbing epic was another retreat from the Nose on El Cap

- 12 hours in a terrible snowstorm and 50 knot winds. We only just

survived. I have been avalanched and dug out and on one memorial kayak

trip I was trapped upside down across a tree and only survived because the

Kayak broke up around me and I popped out among the debris. My balloon

flight over Mt Everest involved an horrific landing at speed among giant

boulders. There was not much left of the gear.

Above Right:

Chris Dewhirst approaching the forth belay on the 1st ascent of Ozymandias,

Mt Buffalo, 1969. Photo By Chris Baxter.

Q: You must also have met, and climbed

with, an interesting array of characters over the years. Can you tell us

about those that stand out as wildly successful climbers, or perhaps

wildly scary or amusing?

One day in 1975 Chris Baxter called me and asked if I would look after a

climber from the US for a weekend at Arapiles. I agreed and found out

later that it was to be ‘hot’ Henry Barber. That weekend I held the rope

for Henry while he not only climbed every hard route at Arapiles he put up

a few new ones harder than anything I could dream of doing. I think he

used about three bits of protection over the entire weekend. Even though I

was fairly fresh from the US and the UK I recognised his skill as

extraordinary (for the times). In great trepidation I met up with Henry in

Telluride (Colorado) a few years later. He was most apologetic that he

couldn’t take me out to a few of his favourite crags because his leg was

broken! A fairly levelling handicap I thought at the time - feeling

greatly relieved.

I met Roland Pauligk when I was about 19 or 20. Roland came on a VCC

climbing course and brought his tree climbing spikes. The first time I

watched Roland climb was a tree at the Mt Rosea camp site. With his strap

on spikes he reached the top of a 50 metre tree in about 30 seconds.

Awesome. Roland escaped East Germany in dramatic circumstances during the

height of the cold war. Roland has an amazing story to tell.

I first met Ian Ross when I was about 18 (later I climbed the East Face of

Frenchman's Cap with Ian and Dave Neilson). Ian had grown up and done some

climbing in the UK and was my age. Within a few days of arriving in

Melbourne he hitched to Mt Arapiles, asked what was the hardest climb at

Araps (at the time it was the Fang first climbed by Peter Jackson and

graded HVS) and then Ian soloed it.

This always stuck with me as very impressive and I tried to do the same on

a crag in the UK. I borrowed Ian’s car and toured some of the gritstone

crags with Ian Talbot and a couple of other likely lads in 1974. On one

crag I asked a group of poms which was the hardest climb and they pointed

out a climb put up by Joe Brown (Emerald Crack) and using a couple of bits

of aid. I announced that I would do it free. After an hour of attempting

this awful climb there were about 100 poms gathered around watching me. In

the end I couldn’t even do it with two bits of aid and I gathered my gear

to leave when one of the climbers asked me my name. To my everlasting

shame I said my name was Chris Baxter, jumped in Ian’s car and headed for

the nearest airport. When times were tough Chris Baxter was always there.

Q: I'd be interested to hear about the

shooting of "Just Another Climb', a drama-documentary shot on location in

New Zealand, reconstructing a mountaineering tragedy. You played a lead

role. Had you much mountaineering experience at that point? How closely

did the film mange to depict the real conditions?

Alan Gledhill died retreating in a storm, trapped on an abseil unable to

recover by climbing back up the rope. Geoff had two terrible nights wedged

in a crevice waiting for the storm to clear before he could continue the

retreat.

At the time Geoff Gledhill was satisfied with the result of the

documentary. Obviously neither Chris Baxter or myself were actors - and at

that level it was fairly ordinary.

It was impossible to convey what it really must have been like for Geoff

and Alan. Neither Chris or myself had spent much time on ice, but the

climb Alan died on was mostly rock. I think filming techniques today could

produce a much more compelling result.

Q: Lets talk about Ballooning, because

obviously this passion has long since eclipsed your earlier interest in

climbing. Can you briefly describe what got you started and ultimately

lead to a successful business (Balloon Sunrise), and such amazing feats as

flying over Mt Everest?

In 1980 I set up a business with Gerry Virtue based in Sydney. It was in

competition with Australian Himalayan Expeditions and Peregrine. The

competition was very fierce and eventually Peregrine bought us out. I

retained the ballooning part of the business and at one stage I had 9

pilots working various parts of the country.

At the time I started ballooning I shared a house in Balmain with John

Tann. John built his own balloon and partly because aviation was in my

blood and partly because of the serendipity nature of ballooning and my

friendship with John I became involved.

Ballooning was a much more practical way of making a living and having

fun. Eventually I sold up the remnants of Balloon Sunrise and in 1988 I

specialised in commercial balloon operations over Melbourne. This was the

most profitable part of the business and the most difficult. As a

passenger carrying business it is the ‘grade 33’ of all commercial

operations anywhere in the world. Only about one in 50 commercial balloon

pilots is up to the task on a daily basis.

Balloons do not have steering wheels and the only way to direct a balloon

is to vary the height of the balloon to take advantage of variations in

wind direction. City flying is very technical and very political. The

balloon has to be steered to a particular football oval over a distance of

(sometimes) 30 km with no rudder. And there are no fallbacks and you have

a dozen passengers on board. The experience is very intense for the pilot.

My interest in climbing and in ballooning merged in a flight over the

summit of Everest. I could see the footseps of Ed Hilary leading from the

Hilary step to the summit.

I sold the business last May and I am currently living on the north coast

of NSW with my wife and a 2 year old.

Q: Okay, generic question time, what's

your favourite crag in Victoria, and all time favourite climb?

My favourite crag (in order) is Mt Rosea, Araps, Bundaleer and Mt Buffalo.

My all time favourite climb is the East Face of Frenchman's Cap.

Q: Do you have a climbing hero/heroine?

John Ewbank and Chris Baxter.

Q: So what does your future hold?

Working on a few ballooning expeditions and being a dad! (and loving it).

In the words of one famous Ausrtralian climber ...’Straight to

grandfatherhood!...

Further Reading: ![]()

Balloon Sunrise

- Details about Chris on his Ballooning website.

Home | Guide | Gallery | Tech Tips | Articles | Reviews | Dictionary | Forum | Links | About | Search

Chockstone Photography | Landscape Photography Australia | Australian Landscape Photography

Please read the full disclaimer before using any information contained on these pages.

All text, images and video on this site are copyright. Unauthorised use is strictly prohibited.